The fascinating story of the Desert Sculpture Park on the brink of the Ramon Crater is related to settling of the Negev, the recognition of the Israeli art world and Israeli artists, the artists’ deep connection to the history of the land and its landscapes and to the development of Israeli art.

Background

In 1959 the first international sculpture symposium was held in St. Margarethen in Austria. It was initiated by the Austrian sculptor Karl Prantl, who, against the background of a feeling of alienation and distance created by the Cold War, wanted to create a dialogue between artists of different countries and nationalities. The symposium also aimed to encourage artists to leave the four walls of the studio or gallery and create art out in the open.

Since then, international sculpture, symposia have become common, and over the years, similar events have been held all over the world, in Germany and France, the United States, Japan, South Korea and Australia. In some places, these symposia have become regular events.

Establishing the Park

In 1960, Israeli artist Kosso Eloul was invited to attend the second international symposium in St. Margarethen. The concept of creating art in an open space and meeting artists from different nationalities captivated him and he thought that holding a symposium in Israel could give the Israeli art world international recognition. On the basis of relations established between him and the artists he met at the event in Austria, Eloul invited seven of them, who were to become well-known artists over the years, to participate in the first ever sculpture symposium held in Israel. (The catalog of the event says that the artists were selected by a committee of experts, composed especially for this purpose, but in fact Eloul knew every one of them himself from the Austrian symposium). In addition to artists from around the world, Eloul invited two Israeli artists who had just begun to make a name for themselves in the Israeli art world: Dov Feigin and Moshe Sternschuss.

Jegar Sahadutha

The name chosen for the symposium held in 1962 was “Jegar Sahadutha’, and, as written in the symposium’s first catalogue, “came to symbolize an alliance… between artists of various nationalities, who came together to create”. This is the biblical name that Laban the Aramite gave to the pile of stones he erected with Jacob as a memorial of the covenant between them: “Jacob said to his relatives, “Gather stones.” They took stones, and made a heap. They ate there by the heap. Laban called it Jegar Sahadutha (“Witness Heap” in Aramaic) and Jacob called it Galeed.” (Genesis 31: 46-47)

The Aramaic name represents the alliance between “artists of various nationalities” but also symbolizes the ancient connection between the ‘new’ Israeli and the land. In the introduction of the second catalog, the architect Aba Elhanani, Chairman of the Department of Plastic Arts in the National Council for Culture and the Arts, wrote: “Man has always viewed art as an international language that unites and brings people and nations together.”

Mitzpe Ramon was chosen due to its ancient desert landscape, and there is no dispute as to the intensity of the crater’s scenery, which is reflected in the works of all participants of the 1962 symposium. Another reason for the choice for Mitzpe Ramon was that it was “a new, Negev settlement, symbolizing the state of Israel, giving all it has to the flourishing and settling of barren desert land” as the first catalog wrote. Also, because “the Negev is the country’s greatest challenge,” as Elhanani wrote in the second catalog.

Art in itself was of course no less important and was the main goal of the event in Mitzpe Ramon. As written in the first catalog: “Sculptures in an open space bring us closer to art no less than big, significant and expensive museums do.” The economic-tourism aspect was not forgotten either: “There is also no doubt that a sculpture park in the Negev will be a highlight for art-loving tourists.”

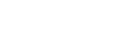

The ten artists who came to Mitzpe Ramon in the spring of 1962 lived in the town in pioneering conditions for ten weeks. During this period, the town’s residents, especially the children, were full partners in the artistic process. Each artist chose the material he or she wished to work with. Five artists (Augustin Cardenas, Kosso Eloul, Moses Sternschuss, Jens Lenasi and Karl Prantl) chose to work in limestone, while each of the others chose different materials: Dov Feigin worked with gravel, Yasuo Mizui with locally-found dolomite; Patricia Diska chose granite brought from Eilat; Josef Wyss worked with basalt and Jacques Moeschal cast in concrete.

The sculptures created at the 1962 symposium are abstract and match the spirit of sculpture art of the second half of the 20th century. Most of them – except for those done by Cardenas and Mizui, which have a surrealist influence; and Feigin’s sculpture, which was influenced by the Canaanite movement – comply with the geometrization style prevailing in European and American art of the 1950s and 60s. The sculptures are shapes in the space, monumental, rising upwards, each standing solitary. All relate to the landscape they gaze upon, but do so in a profound poetic or metaphorical manner.

The Second Phase Initiative

For 25 years the area of the sculpture park was neglected and used as a garbage and construction debris site. Then, in the mid-‘80s, Ezra Orion, a member of Midreshet Ben-Gurion and a renowned artist in his own right, took upon himself to restore the site and reinforce it by adding geometric sculptures around the park created by contemporary Israeli artists.

In his role as curator of the park, Orion recruited the Jewish National Fund, which began clearing the site. For the first stage, Orion invited six artists to join him on the site. These were: Dov Heller, Dalia Meiri, Hava Mehutan, David Fein, Noam Rabinovich and Itzu Rimmer. The curator’s vision, which was in tune with all artists and coherent with their artistic approach, was that the sculptures will strive to create a dialogue with the terrain and that the artists will use local rock from the stone quarries which operated north of the town. Each artist was designated a slot of 100×100 meters on the edge of the cliff.

The first tour of the region was conducted in the spring of 1986, and each artist chose the ground on which to create his or her piece. Later that year, the artists visited the area several times to select the particular stone to work with; thirty rock segments were allocated to each artist and sculptor. The sculptures themselves were set in place over a period of two weeks in August 1986 with the help of heavy machinery belonging to the Jewish National Fund.

In 1988, three more sculptures were erected. They were made by Noam Rabinovich, Bernie Fink and Salo Shaul (their construction had been delayed for various reasons). In 1995, as part of the “Coexistence” event in Mitzpe Ramon, initiated by artist Yigal Ozeri and with the help of Orion, Micha Ullman constructed his work “Cupmarks”.

The visitors’ experience

Visitors to the park will easily notice the differences between the 1962 statues and those of the 80s, particularly in their basic approach to the artistic process. The first stage artists worked all in single stones towering upwards. Although all the sculptures were modernist and abstract, the artists carved or chiseled their works out of the stone itself, based on the classical approach of diminution, working mainly with a hammer and chisel. Sculptors of the 80s used mainly raw rock – the only manmade trace being the tools of the quarry. Most of the sculptures were created by physically placing the stones on the ground, using the terrain where the sculptures were placed, and some of the works even seem to merge into the landscape itself.

Another difference is reflected in the choice of stone: the first stage artists chose a variety of raw materials, including limestone, granite, basalt and even concrete. The second stage artists used massive local dolomite rock. The difference in choice of materials is also indicative of the difference in the basic attitude towards landscape sculpting. Despite the impact of the sublime landscape of the crater on their works, the 1962 symposium participants were mainly interested in the work of art itself, less in its relation to its placement in the specific environment. In 1986, the artists agreed upon a premeditated approach to the works: that the scenic, human and geological environment equals personal, artistic expression. Most of them indeed converted the shape and structure of the surface into an integral part in their work.

In the catalog of the park published in 1988, Orion wrote: “The Negev Highlands has thousands of sites with traces left of human existence, built from local stone, in a low, horizontal manner, some are existential … and some spiritual.” He also expressed his view on the essence of figurative art: “Sculpture is the design of masses by the forces of space and time. There is tectonic sculpture, aeolian sculpture, volcanic sculpture, meteoric sculpture the Ramon Makhtesh is the result of tectonic and erosive sculpture, over millions of years. The park is a way of connecting the human hand to this massive sculptural process.”

For the visitor walking through the park, Orion’s poetic words are translated into a genuine experience: the breathtaking view and the sculptures, from both stages, force one to contemplate mankind’s being and insignificance in light of the awesomeness of Creation.

Renovation of the Park

In 2016, the Ministry of Tourism, via the National Tourism Company and in cooperation with Mitzpe Ramon local council, initiated the continuation of the development of the park. The sculpture park is one of the links in the chain of promenades and scenic trails on the edge of the crater’s cliffs, which begins at Har Hanegev Field School, continues to the views from Camel Hill and the Albert Promenade, toward the Visitors’ Center and the eastern trail around the Beresheet Hotel, leading up to the Desert Sculpture Park.

The development of the landscape has two objectives: in the daytime, to create a unique and alluring experience, in the spirit of the location, where the visitor is exposed to the sculptures in an open museum. At night, dark sky conservation makes way for a rare spiritual experience of man in the desert under millions of stars. In addition, the development will also make the park accessible for the disabled.

The renovation project includes regulation of parking spaces, planting trees, creating paths and routes for visitors including rest points and information about the sculptures and the rehabilitation of tainted areas. A new, special observation point on the cliff edge over the crater is also being developed. All this will create new opportunities for artists, tour operators and the community.

Author: Itzu Rimmer